Morgan Meyer and Franck Cochoy

The health crisis has radically transformed the existence of the mask. Before the crisis, it was hardly visible in public debates and little worn by the public. Uncertainties and debates have proliferated as the crisis unfolds and the mask is an object that crystallises health, economic and social issues. What is most surprising is the following paradox: an object that is a priori very simple, cheap, and easy to produce… has been transformed into a coveted object, a controversial object. To understand this tension between mass object and singular object, we need to “unstitch” the mask in order to tease out its different political dimensions.

[Geopolitics] The mask quickly became a geopolitical object. The United States was accused of having diverted masks intended for other countries. China relied on “mask diplomacy” by delivering them to nations of its choice, while at the same time seeking to improve its image throughout the world. The German Chancellor called for a more “sovereign” European Union with regard to the production of masks, while deploring the over-concentration of mask production in Asia. All these examples are evidence that political and economic relations between countries have been put to the test because of the shortage of masks at the beginning of the pandemic.

[Governments] At the national level, many governments have made a U-turn regarding the wearing of masks, including Germany and France. Initially, governments ensured that wearing masks was of little use. Today, wearing a mask is recommended in some countries and compulsory in most others. In the United States, the Biden administration clearly states its preference for the mask.

[Agencies] Agencies have also been involved in the debates around the mask. On the one hand, the WHO, which functions as a multilateral international agency, has been accused of pro-Chinese bias and of reversing its position regarding the use of masks. On the other hand, the Swedish Public Health Agency acts in total independence: the Swedish State scrupulously follows its recommendations, including the absence of a lockdown and the non-compulsory wearing of masks, at the risk of a certain abandonment of the autonomy of the political. Never has the relationship between expertise and politics been so troubled.

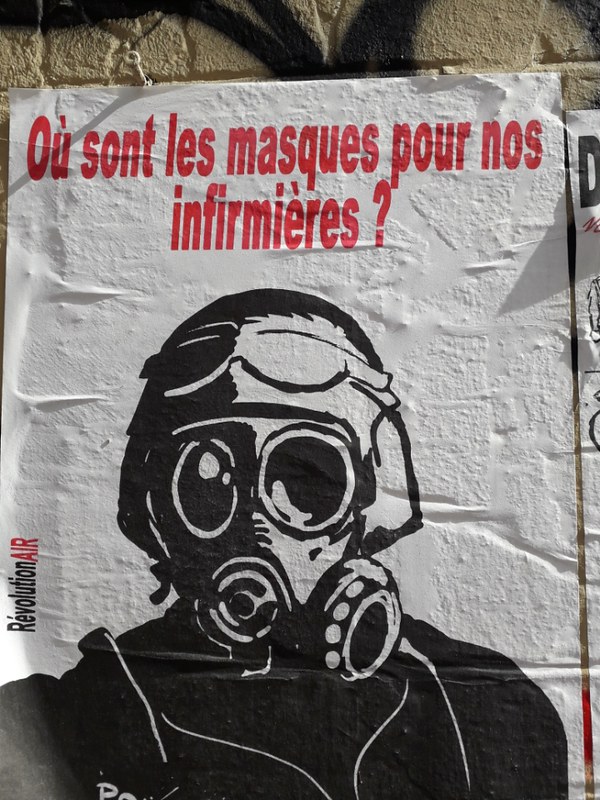

[Supply] This is a question that probably everyone asked him/herself at some point: how come that masks could be encountered in the public space, whilst they were missing for carers? Behind the suspicions of theft, black markets and misappropriation of hospital equipment, we discover more prosaic explanations: precautionary purchases, remnants of previous epidemics, compassionate donations from caretakers, and do-it-yourself (DIY) masks. The shortcomings of professional logistics were quickly tackled by citizen logistics. The debate on supply has just been relaunched with discussions about the usefulness – or even the necessity – of FFP2 masks, as in Germany and Luxembourg.

[Oneself] Faced with the shortage of masks at the beginning of the pandemic, a whole range of DIY masks flourished. Tutorials for how to build masks oneself have been relayed in many media and social networks or by professional associations or hospitals. The techniques and materials used to make these masks vary enormously, from the use of paper towels and handkerchiefs to the use – even 3D printing – of plastic and the use of different types of fabric and clothing. As DIY masks became more widespread, controversies about their reliability and effectiveness have multiplied. While the French Minister of Health recently recommended that cloth masks should no longer be used in the face of new variants of the virus, the Academy of Medicine and the WHO contradict this standpoint: the variants are transmitted in the same way.

[Price] The shortage of masks has overturned traditional market regulation. As in the case of organ donation, it required abandoning the principle of the highest bidder and establishing moral allocation rules. The shortage made it necessary to introduce price controls and also led to the emergence of a gift economy, very often associated with self-production, at odds with the manufacturing and market economy of the “world before”.

[Ecology] Finally, the ecological dimensions of the mask should not be underestimated. At the beginning of the pandemic, the disposable surgical mask – manufactured, standardised, certified, globalised, with measurably higher efficiency – appeared to be the optimal solution. But like all modern products, this solution has its dark side in terms of wasted resources and environmental contamination. Therefore, home-made and/or washable and reusable masks, that are less efficient but more responsible, offer other choices for the “world after”. Over the past few months, however, a change can be observed: disposable masks seem to have become the “norm” while home-made masks are becoming increasingly rare.

The mask is an object that opens our eyes: at last we pay all the attention needed to the things we wear! We should have the same knowledge, the same ethics, the same concerns about our shirts, glasses, helmets, plastic bags, etc. Thus, beyond a certain frustration that we may feel – the mask perturbs us both physically and politically – we should feel a kind of wonder: this object that is so light has in fact an enormous political weight. It teaches us a great deal about the political texture of things.

Paris, January 28, 2021

Morgan Meyer, CNRS Research Director, Centre de Sociologie de l’Innovation (i3), Mines ParisTech, PSL

Franck Cochoy, Professor of sociology at the University of Toulouse Jean Jaurès. Senior member of the Institut Universitaire de France

This article has been written in the scope of the Maskovid project, a collective investigation supported by the ANR and conducted by a group of researchers in sociology from the universities of Toulouse and Nice and the École des Mines de Paris, Madeleine Akrich, Cédric Calvignac, Roland Canu, Franck Cochoy, Anaïs Daniau, Gérald Gaglio, Alexandre Mallard and Morgan Meyer.

Read also:

Alexandre Mallard et Anaïs Daniau, Ces petits commerçants qui ont résisté à la crise… , The Conversation, 21/09/2020.

Gérald Gaglio, Alexandre Mallard et Franck Cochoy, Des « invisibles » tombent le masque, The Conversation, 17/05/2020.

Photo #1 Credit: 7C0, “Fuck Covid”, juillet 2020. (CC BY 2.0)

Photo #2 Credit: Jeanne Menjoulet, “Photo-souvenir du temps du confinement coronavirus, avant la grande manif des soignants du 16 juin 2020” [‘Where are the masks for our nurses?’, Souvenir picture of the time of the coronavirus lockdown, before the carers’ protest on June 16, 2020], Marseille, May 2020. (CC BY 2.0)