Firefighters against the biological threat:

Making the invisible visible

through an aesthetics of efficiency

By Maria Viola Zinna

Maria Viola Zinna is a member of the CSI-i3 team, led by Morgan Meyer, which is a partner in the DEFERM project – “Decontamination measures to restore facilities and the environment after a natural or deliberate release of pathogenic microorganisms”, alongside IP Institut Pasteur, SPI / LI2D CEA Centre VALRHO, BDRFD Bouches-du-Rhône Fire department, ADM ADEMTECH and CETEP. The DEFERM project (2021-2024) is funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

Maria Viola Zinna, 2024. CC-BY-NC-SA

Firefighters are the first biosafety responders to a situation involving the release of hazardous biological agents. Biosecurity consists of a set of measures designed to protect public and national health (Brunette, 2013) by preventing the spread and adverse effects of potentially pathogenic organisms.

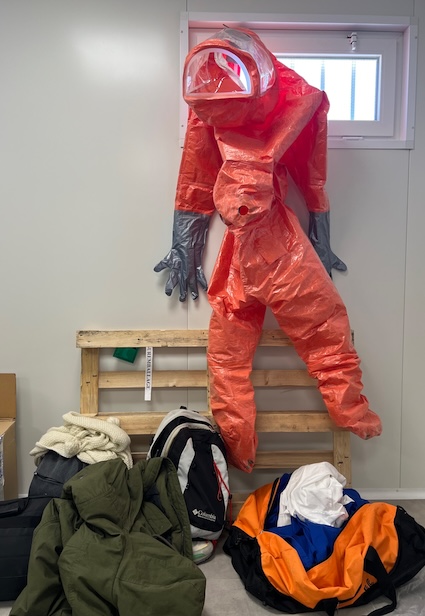

From protective suits to signaling devices, intervention in “biohazard” situations is materialized through heightened visibility, as can be seen in photos #1 and #2. In this article, we consider the role of aesthetics in biosecurity as an agent of prescription and coordination, or to put it in other words, the aesthetics of organization and efficiency (Taylor and Hansen, 2005). To analyze this material culture (Miller,1987), we have drawn on the work by J. Denis and D. Pontille (2010) on signage objects, focusing on four characteristics taken into account by these authors: the use made of these objects, their main functions, their aesthetic qualities and their positioning in relation to surrounding objects.

Biosafety interventions are situations that require training, especially as they are rare (an average of 60 interventions a year in France) and the unpreparedness of firefighters could be a source of danger. To address this danger, the DEFERM project set out to develop a structured exercise based on a fictitious scenario involving the care of a person infected with the Ebola virus. The “official” exercise took place in public on March 1, 2024. The day before, February 29, was devoted to setting up the scenario, as well as to workshops to teach firefighters, the main users of the new equipment, how to use it. It’s on the observation of this day that we focus.

Dealing with the invisible

Captain Borselli, zonal biohazard referent, invited researchers from the DEFERM project, namely the biologists from the Pasteur Institute as well as the sociologists from the CSI and the University of Freiburg’s Institut für Soziologie, at the training center as observers and to take part in workshops and demonstrations. A fire truck, positioned just a few meters away, awaits the signal. The green light is given, the siren sounds, and the vehicle rushes off.

Maria Viola Zinna, 2024. CC-BY-NC-SA

Five firefighters emerge from the truck with an air of gravity, yet a confident gait. The first three are dressed in gray reflective protective suits. These are Tychem® 6000 F biological protection suits, which we are told are resistant to liquid penetration (o-xylene “EN ISO 6530”) and therefore provide a chemical and biological barrier. The suit covers the body up to the face, in a visibly tight hood, leaving only one or two centimeters of skin exposed between the middle of the forehead and the plastic goggles protecting the eyes. Droplets of sweat have already begun to form on this tiny patch of bare skin. The FFP3 mask is visible through the goggles. Beneath the plastic suit are boots whose shape we can only guess. We know that there are two women among them, but we can’t tell them apart from the men. Finally, the hands, the main actors in this operation, are protected by green gloves similar to surgeons’ gloves, with nothing human about them but an automaton-like silhouette.

Grey-suited silhouettes demarcate the intervention zone by installing posts and red-and-white tape. Using the bright yellow tape marked “biohazard” (photo #1), they separate potentially infected areas from safe zones, in other words, “dirty” from “clean”. The grey-suited silhouettes set up a yellow carpet with the words “entrance” and “exit” at each end. Just past the “entrance” word, they set up a basin full of bleach. An obligatory step, this bath will be used to decontaminate the boots. The area just before the “exit” word is dedicated to cutting off the protective suits that will remain in the risk zone.

Finally, two bright red and yellow tents have been erected inside the danger zone at two diagonal ends of the space. The role of the first is to receive and isolate the victim, who will be taken care of by specialized personnel. The other will be used for analysis, carried out by grey-suited personnel, that will allow the appropriate decontamination procedures to be launched.

Orange-suited personnel (also in Tychem® 6000 F suits) are at the heart of the action. Like those in grey suits, they are equipped with special gloves and boots, as well as full face protection in the form of a cosmonaut-like helmet – the only one that guarantees maximum protection. They are responsible for the “nozzles” used in the decontamination procedure to spray a disinfectant foam effective against all biological agents, which was developed by CEA Marcoule as part of the DEFERM project.

During the exercise, personnel in grey suits appear to oversee containment, while those in orange suits will appear to oversee decontamination. The following day, however, personnel in both colors will perform the same tasks, the idea being to familiarize the firefighters with all the procedures.

When safety is mastered by aesthetics

Our description highlights the aesthetics of the material culture of biosecurity and how it performs an ordering function in potentially dangerous and uncertain terrain. Its efficacy is conceived entirely through four determinant agents.

The first is the chromatic aspect of these objects: the very bright visual hues (yellow, red, and orange) serve to create a strong contrast with the direct environment. As R. Schmutz, D. Borselli and their colleagues point out, “the challenge is to maintain a level of vigilance in the face of an invisible risk and ever-increasing operational overload, leading to agent fatigue and risk trivialization” (2020: 344). This high contrast thus acts as a catalyst for perception encouraging vigilant behavior in the field. Bright colors actively provide information for decision-making, enabling the articulation of cooperation between firefighters, their environment, and the efficient distribution of tasks.

The second agent is the materiality of these objects, i.e. their reflective nature. Amplifying the first agent, it provides an all the more striking contrast with the environment as it transforms light into a powerful visual signal, enabling visibility in all circumstances, whether in poor weather conditions or in low light.

The third is the shape of signage objects (tapes, poles), which gives them a segmentation function. Their shape is in itself sufficient to indicate their meaning, making visible and separating safe from contaminated areas, and distinguishing degrees of danger from areas in which firefighters are operating.

Finally, the fourth agent deals with the management and spatial arrangement of objects and people. Far from being fixed, it depends on the analyses, and involves the three previous agents: color, materiality and form act together to segment space, signal danger and coordinate actions.

Making the biological threat tangible and manipulable

The protective function intended by this material culture (Autorité de Sureté Nucléaire, 2023: 24-25), while guaranteed by the physical qualities of protection against the outside world (protective gear, decontaminants), are also enabled and mastered through visual codes (color, material, shapes, space) that establish the management of this safety

These color schemes, materiality, and shapes in space explicitly signal and contribute to the scenarization of the danger in which firefighters find themselves. By making invisible hazards visible, risk can be brought under control, as its communication enables the coordination of firefighters’ actions with respect to the environment, each other, and the biological risks they face. In this sense, the aesthetics of biosecurity transforms physical space into a dynamic field of communication. It makes the invisible visible and enables firefighters to act effectively.

The main point to emerge from this fieldwork is that the aesthetics of biosecurity effectiveness is based on very specific roles: (i) a protective role against pathogens; (ii) communicating an organization through codes warning of hazards; and, finally, (iii) the management of this organization by the firefighters themselves, including the management of biological analyses performed in the field, enabling them to act in the face of uncertainty. These three elements transform potential threats into tangible and therefore manipulable elements.

References

Autorité de Sureté Nucléaire, 2023. Guide National d’intervention médicale en situation d’urgence nucléaire ou radiologique, 202 pages.

Brunette Rayan, 2013. Biosecurity: Understanding, assessing and preventing the treat. John Wiley & Sons Inc, Hoboken.

Denis Jerôme, Pontille David, 2010. Petite sociologie de la signalétique. Les coulisses des panneaux du métro. Presse des Mines, Paris.

Miller Daniel, 1987. Material Culture and Mass Consumption. Oxford, Blackwell.

Schmutz Robin, de Villepoix Maya, Vally Abdoullah, Gay Michaël, Galy Stéphane, Borselli Diane, 2020. Prise en compte opérationnelle du risque biologique chez les sapeurs-pompiers. Médecine de Catastrophe – Urgences Collectives, 4 (4), 341–344.

Taylor Steven S., Hansen Hans, 2005. Finding Form: Looking at the Field of Organizational Aesthetics. Journal of Management Studies, 42 : 6 September, 0022-2380.

Photo credit: Photos taken by Maria Viola Zinna on February 29, 2024 at the Departmental Training Center of Bouches du Rhône fire department.